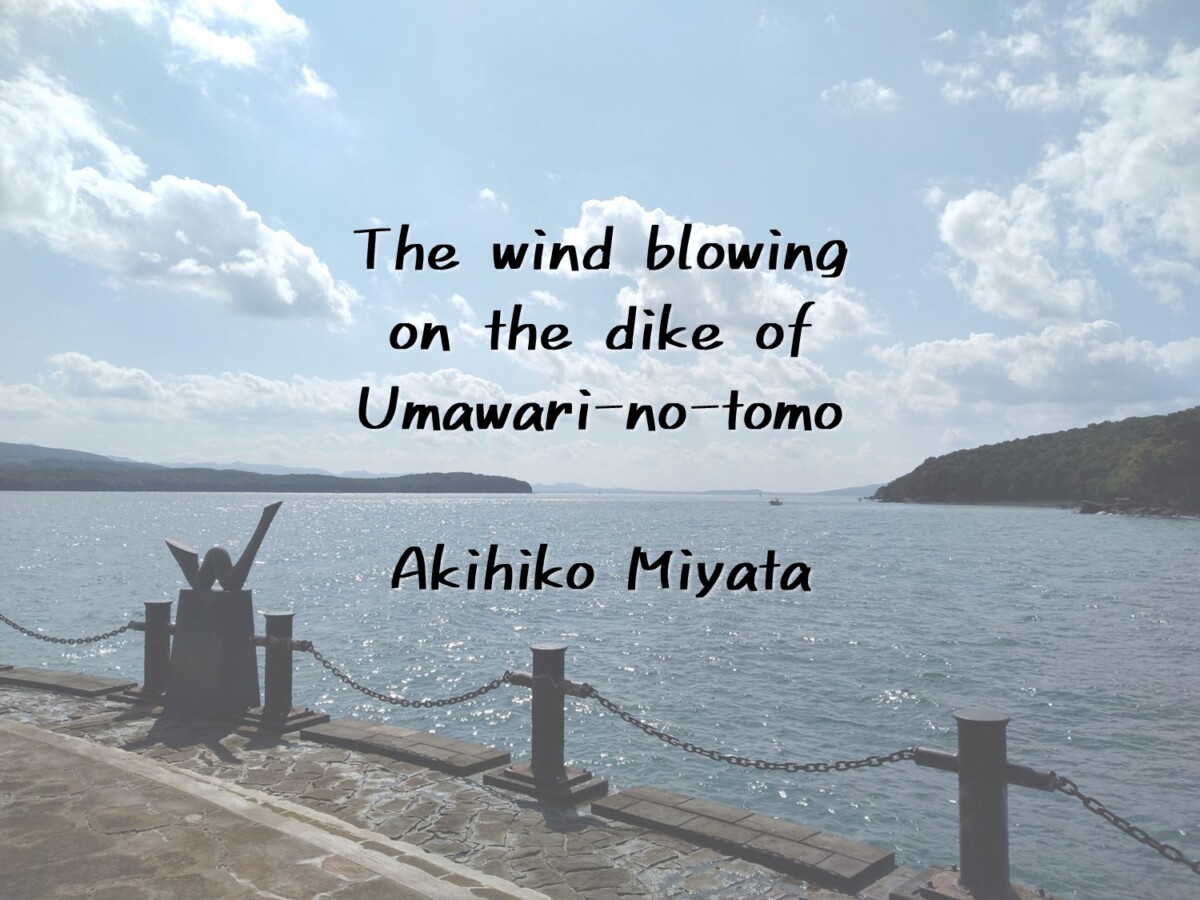

大廻りの塘に吹く風/宮田晃碩

私が水俣に出会ったのは、石牟礼道子『苦海浄土――わが水俣病』を通してだった。

父の実家が熊本で、幼い頃から盆や正月には帰省していたので、熊本弁は言葉の意味が分かる前からぼんやりと聞いていた。その懐かしい響きが「聞き書」として目の前に現れたとき、私は自分の知らない幼時の記憶に出会ったような感動を覚えたのである。

もちろん熊本といっても地域は違うから言葉の細部も異なるだろう。ただ私にとってその言葉は、自分が標準語を覚える以前に、あるいは生まれる前に聞いていた言葉のように思われた。そのときから水俣は、片思いの故郷のようなものになってしまった。

It was through Ishimure Michiko’s Kugai jōdo (Paradise in the Sea of Sorrow), a literary work which depicted the sufferings and lives of the victims of Minamata disease, that I first encountered Minamata. What especially captured my heart was the kikigaki – the recorded oral testimonies – because the dialect sounded surprisingly familiar to me. My father was born and raised in Kumamoto, and I often visited my grandparents there as a child. I would hear the adults speaking in the Kumamoto dialect, even though I didn’t fully understand it at the time. The rhythms and tones were deeply embedded in my memory, and seeing them expressed in the written words of Kugai jōdo felt like rediscovering a forgotten part of my childhood. It was as though I found a hometown I had never known.

きちんと水俣を訪れたのは、研究員として所属する大学の哲学研究センターのイベントで、水俣病センター相思社にお世話になったときである。オンライン配信のイベントの前には、相思社の永野三智さんに茂道や湯堂、乙女塚、チッソ正門前、百間排水溝、水俣湾埋め立て地(エコパーク水俣)などを案内していただいた。

しかし実はその前に湯の鶴温泉で湯に浸かりながら地元の男性と話したとき、どこから来たかと聞かれて「東京から」というと「じゃあ水俣病のことで来たんだね」と言われ、湯気の向こうの屈託のない笑顔をまえに、私は恥じ入ってしまったのである。それはどうしようもない事実であった。

自分と水俣との出会い方は極めて限定的である。水俣との、この距離は何であろうか。そもそも私が近づきたい水俣とは何であろうか。以来「水俣に行く」と口にするたび、その疑問が胸を去らない。

A few years later, I properly visited Minamata with some professors and colleagues. The main purpose of the trip was an online event broadcast from Minamata, organized by the university’s philosophy research center where I work as a research fellow. Before the event, Nagano Michi-san from Sōshisha kindly guided us to several significant locations, including Modō, Yudō, Otome-zuka, the main gate of the Chisso factory, the Hyakken drainage canal, and the reclaimed land of Minamata Bay (Eco Park Minamata). One of my most vivid memories during the trip, however, occurred earlier, when we were soaking in the hot springs at Yunotsuru and started talking with a local man. He asked us where we were from, and when we replied “Tokyo,” he said, “So, you’re here because of Minamata disease” with an untroubled smile. It was an undeniable truth, and I felt a deep sense of shame. “Minamata disease” is what connects Tokyo to Minamata, but it is also what creates a distance between them. Where do I stand and why am I trying to approach Minamata? These questions have lingered in my heart ever since that encounter.

その後私は、たまたま友人が企画していた「水俣スタディツアー」に参加し、2回目からはその企画・運営側にまわることになった。これはGlobal Shapers Community Fukuoka(GSC福岡)という団体のメンバーが企画したもので、水俣病の歴史や現在に続く問題、地域での取り組みなどを現地で学ぶことを目的としている。私が『苦海浄土』を論文で取り上げたりして水俣に関心を寄せていることを知って、友人が声をかけてくれたのである。そのような次第でいつのまにか、私は半年に一度ほど水俣を訪れるようになっていた。

Lately, I have been visiting Minamata two or three times a year, mainly because I joined a team that organizes study tours there, offering younger generations opportunities to learn about environmental issues, human rights, and social justice. The team was originally formed by members of the Global Shapers Community Fukuoka. An old friend of mine, who was a member of the group, invited me to join the first tour because he knew of my interest in Minamata. Since the second tour, I’ve been involved in the organizing side.

相思社の考証館や水俣市内を何度か案内していただき、自分でも折に触れて勉強し、すこしずつ水俣のこと、水俣病のことに詳しくなっていく。それは自分の世の中に対する見方を確実に豊かにしてくれた。そしてなによりここでは一人の人間に立ち返って物事を感じ、考えることができるように思えた。

I have gradually become more knowledgeable about Minamata and Minamata disease through my visits and by studying its history and ongoing issues. This has broadened my perspective on various societal issues and the ways people think. More than anything, when I come to Minamata, I feel as if I’m reconnecting with myself and I’m able to truly reflect and think for myself.

そしてこの前の3月、このスタディツアーを企画している仲間たちで連れだって、ツアーの運営ではなく自分たちの関心の赴くままに、要するに遊びに水俣にいこうということになった。私は資料調査を兼ねて他のひとより一日早く水俣に行くことにした。

Last March, some of the members involved in organizing the tours, including me, decided to visit Minamata – not as organizers, but simply for fun. I decided to go a day earlier because I wanted more time to stay and do some research.

相思社で資料調査をさせていただいた翌日、他の人たちと合流する前に私は丸島漁港にレンタカーを停めて「大廻り(うまわり)の塘(とも)」を歩いた。前日の夜にたまたまお会いした写真家の森田具海さんがおすすめの場所として名前を挙げていたからである。石牟礼道子の作品(特に『椿の海の記』)に惹かれて水俣に移住するに至ったという森田さんが、どんなふうに水俣を見ているのか私には気になった。幼少期の石牟礼をモデルにした「みっちん」が主人公の自伝的小説『椿の海の記』には、大廻りの塘でみっちんが狐に変身しようとする幻想的な場面がある。

The day after I did some document research at Sōshisha, I took a walk along the dike of Umawari-no-tomo before meeting up with the others. The location is portrayed in Ishimure Michiko’s Tsubaki no Umi no Ki (Story of the Sea of Camellias) as a fantastical place where little Mitchin, a character modeled after Ishimure as a child, attempts to transform into a fox cub. Morita Tomomi-san, a photographer I had met the previous night, recommended that I visit this spot.

Here is the scene in Tsubaki no Umi no Ki:

秋の昼下り頃を、芒の穂波の耀(かがや)きにひきいれられてゆけば、自生した磯茱萸(いそぐみ)の林があらわれて、ちいさなちいさな朱色真珠の粒のような実が、棘の間にチラチラとみえ隠れに揺れていて、その下陰に金泥色の蘭菊や野菊が、昏(く)れ入る間際の空の下に綴れ入り、身じろぐ虹のようにこの土手は、わだつみの彼方に消えていた。するともうわたしは白い狐の仔になっていて、かがみこんでいる茱萸の実の下から両の掌を、胸の前に丸くこごめて「こん」と啼いてみて、道の真ん中に飛んで出る。首をかたむけてじっときけば、さやさやとかすかに芒のうねる音と、その下の石垣の根元に、さざ波の寄せる音がする。こん、こん、こん、とわたしは、足に乱れる野菊の香に誘われてかがみこむ。晩になると、大廻りの塘を狐の嫁入りの提燈(ちょうちん)の灯が、いくつもいくつも並んで通るのだと、婆(ばば)さまたちから聞いていた。わたしは、耀(かがよ)っているちいさな野菊を千切っては、頭にふりかけ、また千切っては頭にふりかけてみる。自分がちゃんと白狐の仔になっているかどうか。それから更に人間の子に化身しているかどうか。(第七章「大廻りの塘」)

In the afternoon, these grasses sparkled in rich, golden-brown tones. Their continuous growth was interrupted here and there by thickets of oleasters, whose tiny, vermilion fruits gleamed like pearls. At their roots bloomed an extravagance of blue spirea and chrysanthemum, which glowed in the deepening sunset with such incomparable beauty that the whole dike, already saturated with the radiance of autumn seemed to have turned into a horizontal, trembling rainbow, which grew paler at one end until it merged into the sea. In that magical instant it wasn’t difficult, it seemed to me, to become a white fox’s cub: all I had to do was bend my hands inwards in imitation of the latter’s forepaws and cry “kon, kon” and the metamorphosis would occur. I tilted my head and listened intently: the rustle of the waving eulalias mingled in infinitely sweet, cool harmony with the lap of the gentle waves of the sea breaking against the dike. Kon, kon, kon… I cried again and squatted down among the gold-tinted wild chrysanthemums, which gave off a pleasant scent. I had often heard marvelous stories from the old women in town about foxes’ weddings, when splendid processions passed at night on the dike, illuminating their way with lanterns. Plucking some flowers, I tore off their petals and sprinkled them over my head. Just like the cubs accompanying the wedding procession. Have I truly become one of them or not? Am I successfully pretending to be a human child? (translation by Livia Monnet, except the last two sentences by me)

これは無邪気な戯れのようだけれども、それと同時に幼いみっちんの無常感が表現されているようにも思われる。

Mitchin’s “transformation” may appear to be an innocent play, but at the same time, it seems to reflect young Mitchin’s sense of transience.

『椿の海の記』には、天草などから女郎に売られてきて「いんばい」と呼ばれ、果ては少年に刺殺されてしまった少女のことや、目が見えず心もおかしくなってしまってさまよい歩き「しんけい殿」と囃し立てられる祖母のおもかさまのことなど、この世の悲しみ、苦しみのさまが、みっちんの目を通して描かれている。

Through Mitchin’s eyes, the novel portrays the sorrow and suffering of various people, including a girl sold from Amakusa into prostitution, cruelly stigmatized and eventually stabbed to death by a teenage boy, and Mitchin’s grandmother, O-moka-sama, who lost her sight and sanity, wandering aimlessly through the streets.

そのおもかさまはみっちんの祖父の「本妻」だが、「権妻」である「おきやばん」について、周囲の大人たちが「おきやばんな、前の生か、後の生じゃ、けだもんばい。畜生ばい、ありゃあ。おもかさまを、あのような目に遭わせ申して」と語るのをきいて、自分を可愛がってくれるおきやばんが畜生の化身であるならば、「自分というものはいったい何の生まれ替わりなのだろう」、「いまいるこの世はひょっとして、まだ生まれ替らぬまえの前の生か、それとももう後の生ではあるまいか」とみっちんは考えたりするのである。狐の仔になり替わって、それからまた人間の子に化けるというのも、自分はいま偶々この人間になっているのだと想像することで、自他の生のはかなさを納得しようとする稚い試みのように思えてならない。

O-moka-sama is Mitchin’s grandfather’s legal wife, while O-kiya is his concubine. The adults around Mitchin would say, “O-kiya-sama must have been some kind of beast in her previous life. And she’ll be reborn as an animal again, that’s for sure. No one who had a human face in another life could have inflicted so much pain on O-Moka-sama as she.” Hearing this, Mitchin would wonder, “Whose reincarnation am I?” and “How do I know that the life I am now living isn’t in fact someone else’s former existence, someone as yet unborn? Or maybe I am the reincarnation of someone who passed away and bequeathed me his soul…” Her transformation into a fox cub and then back into a human child seems like an innocent yet poignant attempt to make sense of life’s transience, imagining her current human form as something merely temporary.

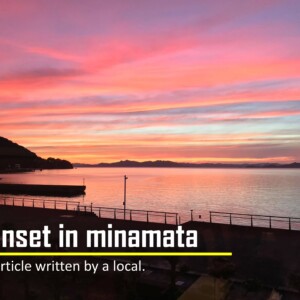

その大廻りの塘を歩いているのは、不思議な感覚だった。塘は完全にコンクリートで固められ、海へゆるやかに張り出したカーブが往時の姿を偲ばせる。すぐ迫っていたであろう海はしかし、埋め立てられたソーラーパネル地帯の向こうに遠のいている。かつて(おそらくみっちんも生まれる前に)塩田だったという陸側は、水溜まりとも言えそうな小さな池を抱いて芒原になっていた。その縁では乾きかけたサボテンがこちらへ向かってコンクリートに凭れ掛かっていたりする。

Walking along the dike of Umawari-no-tomo was a strange experience. The dike was completely covered in concrete, but its gentle curve still hinted at its former shape. The sea, which must have once been close, was now far off, beyond a field of solar panels. On the land side, which had been a salt field perhaps before Mitchin was born, silver grasses swayed around small pools of water, and cacti, half-dried, leaned against the concrete.

町は遠く、寂しい風が吹いていた。このコンクリートの下で、狐とみっちんの夢がまだ眠っているような気がした。それは奇妙な空想だった。過去と現在という隔たりが、『椿の海の記』という小説によって橋渡しされている。しかしそれは小説である以上そのままの現実ではなく、しかもそのなかでみっちんは狐の目を借りてこの世を眺めている。みっちんのその変身はさらに、「婆さまたち」の話に導かれている。現実と記憶、空想、創造が幾重にも絡まり、そのなかで私は大廻りの塘を歩いていた。

I saw the town far away, and a lonesome wind blew. It felt as though the dreams of foxes and Mitchin were still slumbering beneath the concrete. It was a strange thought. The gap between past and present seemed bridged by Tubaki no Umi no Ki, yet that bridge was not a literal reality but a fictional one, for the novel itself is a work of fiction. Moreover, Mitchin gazes at the world through the eyes of a fox, and her transformation is further guided by the tales of the old women. Reality, memory, imagination, and creation intertwined in many layers as I walked along the dike of Umawari-no-tomo.

本当の水俣とは何なのか――私はよそ者だから、そして『苦海浄土』という作品や水俣病事件史という道から入ったから、そう問わずにいられない。けれども求めるべき答えが、誰かの手元にあるわけでもないだろう。その答えは誰も持っていなくて、しいて言えば人びとの夢のなかにあるのかもしれない。その夢をあやすように、波と風がくりかえし打ち寄せ吹いている。本当の水俣とは何なのか。私が近づきたい水俣とは何なのか。波と風にそう問えば、誰もがちがった答えを聞くだろう。私はそれを人と語り合いたいのかもしれなかった。

What is the true Minamata? – I cannot help but ask this question, being an outsider and having entered this place through Kugai jōdo and the history of Minamata disease incident. But perhaps no one holds the answer. If anything, that answer might reside in the dreams of the people, gently cradled by the wind and waves of Minamata. What is the true Minamata? If anyone were to ask the waves and wind, each person would hear a different answer. Perhaps what I truly seek is to share these dreams with others who come to Minamata.

Writer Akihiko Miyata (researcher in philosophy)

ライター/宮田晃碩(哲学研究者)

コメント ( 0 )

トラックバックは利用できません。

この記事へのコメントはありません。